Article by Gwen Jones, Department of Family Services

(Posted 2024 February)

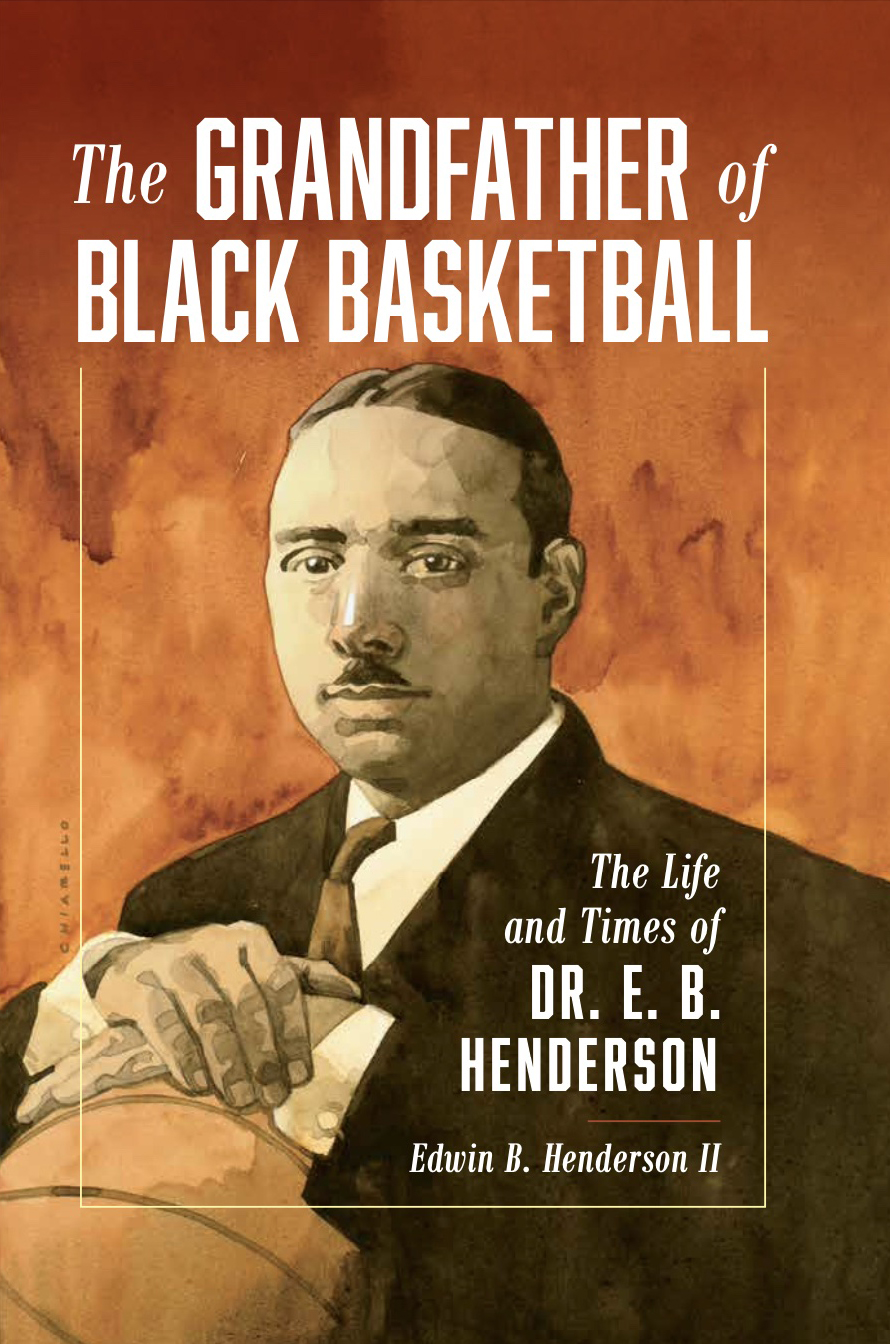

Edwin B. Henderson II is descended from people who made a genuine impact on this world. His grandfather, Dr. E.B. Henderson, who founded the first rural branch of the NAACP, also introduced basketball to the African American community in Washington, D.C., leading to him receiving the posthumous title of “The Grandfather of Black Basketball.” Henderson’s father, Dr. James H.M. Henderson, was an accomplished scientist who made significant contributions to the research of tissue culture through his work with HeLa cells. Following in their footsteps, Henderson is also making an impact. He is the founder of the Tinner Hill Heritage Foundation, whose mission is to document and preserve the history of civil rights in our region. Through his work, the thoughts, actions, and names of those who fought injustice and discrimination will be recognized, recorded, and appreciated by future generations.

Edwin B. Henderson II is descended from people who made a genuine impact on this world. His grandfather, Dr. E.B. Henderson, who founded the first rural branch of the NAACP, also introduced basketball to the African American community in Washington, D.C., leading to him receiving the posthumous title of “The Grandfather of Black Basketball.” Henderson’s father, Dr. James H.M. Henderson, was an accomplished scientist who made significant contributions to the research of tissue culture through his work with HeLa cells. Following in their footsteps, Henderson is also making an impact. He is the founder of the Tinner Hill Heritage Foundation, whose mission is to document and preserve the history of civil rights in our region. Through his work, the thoughts, actions, and names of those who fought injustice and discrimination will be recognized, recorded, and appreciated by future generations.

Edwin Bancroft Henderson II was born in 1955 in Tuskegee, Alabama, into a prominent and accomplished family. His mother, Betty Alice Francis Henderson, who came from a well-known family in Washington, D.C., was a professor of early childhood education at the Tuskegee Institute (now University). His father, Dr. James Henry Merriweather Henderson, was a biomedical researcher and director of the George Washington Carver Research Foundation at the Tuskegee Institute. Henderson, his brother and two sisters experienced a childhood that he describes as “rather privileged.” They spent their summers at Highland Beach, MD, in a house that their mother had inherited from her grandfather. When Henderson was six, the family spent a year living just outside of Paris, France, while his father was on sabbatical. During this time, they traveled extensively, documenting their time in home movies and a story written by his mother. Henderson’s parents ensured that their children received an excellent education. Henderson first attended the Tuskegee Institute Laboratory School before going to Boggs Academy, a college-preparatory academy for African Americans, located in Keysville, Georgia. After that, he attended Tuskegee University, earning a bachelor’s degree in history.

Henderson was named after his paternal grandfather, Dr. Edwin Bancroft Henderson, a civil rights leader who founded the first rural branch of the NAACP to combat segregation and discrimination. While serving as director of health and physical education for Washington, D.C.’s African American schools, he organized the first athletic leagues for African Americans, introducing basketball on a wide scale to the African American community. This work included founding associations to train and organize African American officials and referees. He was a published author of “The Negro in Sports” and “The Spalding Handbook,” between 1910-1913, which he also edited. The bulk of his writing consisted of thousands of letters to the editor and articles he wrote for the National Negro Press Association between 1920-1970.

From the very beginning, Henderson was the apple of his grandfather’s eye. He especially enjoys telling the story of how he came to be named after his grandfather. When he was born, his grandparents traveled from their home in Falls Church, VA, to Tuskegee, AL, to meet their new grandson. Henderson’s parents shared that they intended to name the baby Dave Merriweather Henderson. Upon hearing this, his grandfather took to his bed and a doctor was called, who confirmed that he was very ill. Concerned, James and Betty decided to name their new son after his grandfather. After learning of the name change, his grandfather “threw off the covers, came downstairs and got something to eat. He was fine,” shares Henderson.

In 1965, Henderson’s grandparents moved from Falls Church to Tuskegee, living in an in-law apartment in the family’s home. Because Dr. James Henderson often worked long hours conducting his research, Henderson’s grandparents helped raise their grandchildren and their presence was welcome and appreciated. Spending time with his grandparents, Henderson developed a love for African American culture as well as a love for sports. They also modeled the importance of building good character.

Henderson’s fascination with photography began when he was a teenager. Every Christmas, his family developed photo postcards in the darkroom at the Carver Foundation to send to friends and family. Learning how to process film and print photographs led him to begin shooting his own photos in high school and college. While he was a student at Tuskegee, he had two photos accepted into a United Negro College Fund exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This led him to enroll at Brooks Institute in California, where he earned a degree in photography. Moving to Oakland, California, he studied Television Engineering, and spent the 1980s working in the field of photography and television.

While still living in California, Henderson began teaching in Compton, and continued to teach there for five years. Eventually, he returned to Tuskegee University, earning a master’s degree in counseling education. Wishing to travel, he applied for and received a fellowship, and spent a year at a university in Nairobi, Kenya, before returning to the US and moving into his grandparents’ home in Falls Church in 1993.

After moving to Falls Church, Henderson joined Fairfax County Public Schools. He initially worked as an elementary school counselor before teaching US History at Luther Jackson Middle School for 12 years. His favorite part about teaching was interacting with his students. “Some people say I was crazy because middle school is such a rough time, but it’s also a very exciting time with a lot of change,” he says. Henderson enjoyed sharing the history of civil rights with his students. “I think it was good to teach children diverse and inclusive history and I found the students very receptive to it. Whereas the other teachers and many of the administrators, not so much,” he shares.

In 1997, Henderson founded the Tinner Hill Heritage Foundation, whose mission it is to preserve and celebrate the early civil rights history of Falls Church, Fairfax County and Northern Virginia. One of the earliest events sponsored by the foundation was the Tinner Hill Music Festival, which has grown from a community-based street festival to a festival that routinely books national and international musicians. Another early initiative was the construction of the Tinner Hill Monument in 1999, a granite arch honoring the people of Tinner Hill and the NAACP’s first rural branch. Henderson credits the City of Falls Church and the Fairfax NAACP with helping him make the foundation a reality.

Although he had been considering it for some time, in 2005 Henderson embarked on a campaign to get his grandfather inducted into the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame. He believed the honor was long overdue given his grandfather’s work to introduce and promote the sport to the African American community in Washington, D.C. Henderson’s initial nomination packet consisted of a 138-page booklet detailing his grandfather’s work and included letters of recommendation from Henry Louis Gates and Earl Lloyd, the first African American to play in the NBA. His grandfather didn’t get in that first year, or in subsequent years despite Henderson making a video the next year, then updating the video the following year. Eventually, the committee, led by Manny Jackson, created a special category to induct African American pioneers into the Hall of Fame. In 2013 Henderson learned that his grandfather had finally been accepted into the Hall of Fame. Having experienced a difficult year, even learning the good news via tweet from sports journalist David Aldridge didn’t dampen his joy. “It was exciting. I felt proud. I felt vindicated, you know, all these emotions came to the surface,” he says.

From his experience of trying to get his grandfather included in the Basketball Hall of Fame, it was clear to Henderson that few people knew of his grandfather’s significant contributions to the sport. The idea of writing a book about his grandfather occurred to him about 10 years ago but became a serious pursuit five years ago. After his publisher, Roman and Littlefield, accepted his proposal, the real work began. Henderson describes the process as a journey where he learned a lot along the way. “A lot of people think that once you turn in your manuscript that everything is done with; there was probably as much work after the submission as there was getting the manuscript done,” he says.

While conducting research for his book, Henderson greatest source material came from a cardboard box found in his attic. At the time of his grandfather’s death, someone had packed the contents of his file cabinet in the box and stored it away. Inside was a treasure trove of materials. “That box contained things that no one else had, like the letters from Spaulding regarding the publication of the handbook, the contract from Carter G. Woodson to write “The Negro in Sports,” scrapbooks with photographs that no one else has,” Henderson shared. The box also contained many of his grandfather’s writings, which he used extensively in his book, saying, “A lot of the book is in my grandfather’s words, not in mine. I let him speak to what he did, rather than for me to just say what he did. I think that makes it a little bit more powerful as well.”

“The Grandfather of Black Basketball: The Life and Times of Dr. E. B. Henderson” will be released on February 20. Henderson anticipates that his job for the foreseeable future will be promoting his book. A book release party, featuring an author talk and book signing, will take place on March 9 from 1-2 p.m. at Mary Riley Styles Public Library in Falls Church. Visit mrspl.org/event/eb-henderson-ii-grandfather-black-basketball-14624 for more information and to register.

Beyond promoting his book, Henderson looks forward to a busy 2024. The 30th annual Tinner Hill Music Festival will take place on June 8 at Cherry Hill Park. Performers will include Grammy award winning artist George Porter, the Blind Boys of Alabama, and more. Tinner Hill is also working with the City of Falls Church on two new initiatives. The first is a mural project along South Washington Street in Falls Church. The mural will include the message “Welcome to Tinner Hill” and the unveiling is planned to take place on Juneteenth. The second initiative will designate a portion of South Washington Street in Falls Church as the Tinner Hill Historic and Cultural District.

This article is part of the Golden Gazette monthly newsletter which covers a variety of topics and community news concerning older adults and caregivers in Fairfax County. Are you new to the Golden Gazette? Don’t miss out on future newsletters! Subscribe to get the electronic or free printed version mailed to you. Have a suggestion for a topic? Share it in an email or call 703-324-GOLD (4653).